Ideas + Insights

October 2, 2023Understanding Hostile Architecture: The Cause and Effect of Restricting Public Space

What is Hostile Architecture?

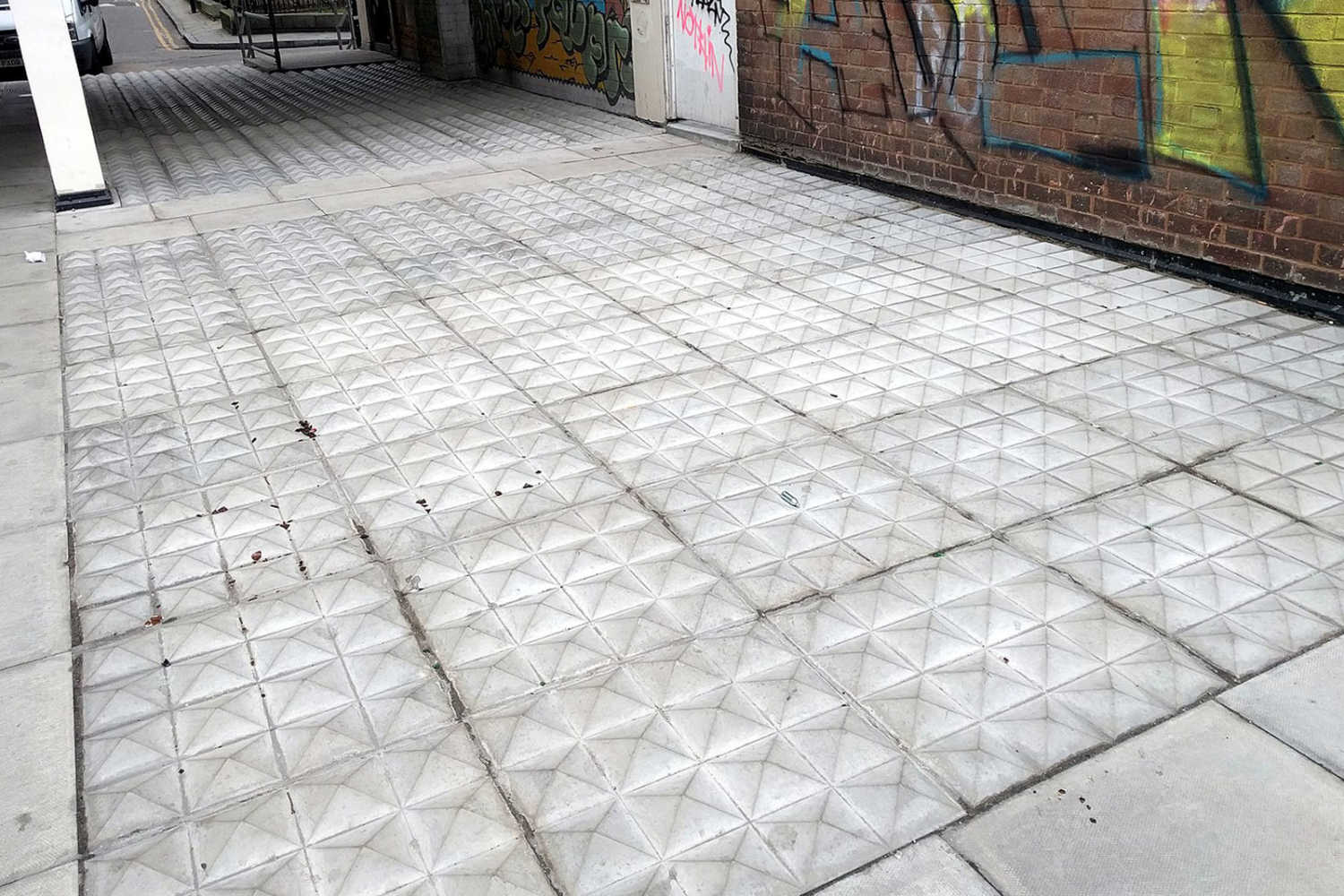

Hostile architecture, also known as defensive architecture or exclusionary design, is an urban design strategy in which public spaces and structures are used to prevent certain activities or restrict certain people from using those spaces.

Many of these restrictive design elements have been aimed at those experiencing homelessness, and the resulting conflict has increasingly gained media attention.

In Portland, Oregon, strategically placed bike racks and planter boxes line sidewalks to keep unhoused individuals from being able to camp or rest in those spaces. In New York City, architects were denied a bid to shrink the vestibule of a historic building now owned by Tom Ford to make the building “less likely to be occupied” by unhoused people. And, in Connecticut, House Bill 6400 was introduced to ban “hostile architecture” all together in public spaces.

Yet while much of the current focus on hostile architecture centers on controversy involving those experiencing homelessness, these design elements are rooted in historic inequities and have been implemented in every area from landscaping to street planning in cities around the globe. The ideals driving the practice insidiously reinforce segregation, disinvestment and inequity across the American landscape.

“In many of the communities where the Neighborhood Design Center works, vestiges of prior hostile design interventions leave public spaces devoid of healthy vibrant public life.”

— NDC Deputy Director Briony Hynson

Briony continues: “While each community has a different combination of factors, we see time and again the long term negative impacts of designing to exclude.”

While the detrimental effects of exclusionary design are long-reaching, organizations like NDC and others recognize both the depth of the challenges these practices present and the imperative to initiate change.

Bloomberg Philanthropies announced Baltimore as one of eight U.S. cities selected to receive a $1 million grant through the 2023 Bloomberg Public Art Challenge, a program that brings people together to address important civic issues through public art.

“Inviting Light,” a series of light based pubic art interventions, will be led by renowned artist Derrick Adams and supported by a collaboration between the Mayor’s Office, Central Baltimore Partnership, and the Neighborhood Design Center. This challenge creates an opportunity to counter some of hostile architecture’s impact in the city through lighting interventions designed to foster safety and inclusivity in Baltimore’s Station North community. Learn more about the project here.

In the subsequent sections of this article, we will delve into the driving forces behind hostile architecture, the complexities involved in addressing it, and the steps forward we have made in finding solutions and creating positive change.

The Local Perspective

City leaders and real estate developers frequently deploy hostile architecture as an attempt to prevent or restrict specific human activities or behaviors in public space.

Examples exist throughout Baltimore City and in Prince George’s County, where most of Neighborhood Design Center’s work takes place. In downtown Baltimore, it’s easy to walk for blocks next to concrete walls with no commercial storefronts or windows at the pedestrian level.

Hostile architecture can be seen in window sills with spikes or public parks with high fences, locks, and few trees in order to prioritize law enforcement’s view of what is happening in the park. Even natural elements, like thorny plants, are often planted at the ground level of buildings to prevent access to windows.

“There are lots of these examples of the way that seemingly neutral elements of the built environment really do shape who feels comfortable and who’s allowed to move through certain spaces,” says Merrell Hambleton, NDC Program Manager of Arts Planning and Cultural Programming.

The issue extends from the surface level to the systemic. Baltimore City’s Greenmount Avenue is one example of how interventions like dead ends, bollards, and one way streets were historically used to separate the poorer, majority African American neighborhoods from the adjacent wealthier, whiter neighborhoods by preventing cars from moving between the two. The hostile design creates a separation that is not just physical, but is reflected in the stark contrast in health indicators between the adjacent neighborhoods and their residents.

In Prince George’s County, NDC is working with the community of North Brentwood to address a historic remnant of hostile architecture that had divided the predominantly Black town from the neighboring majority-white community for decades. The Barrier was once a traffic barrier that served as a physical divide between the two communities. The North Brentwood community worked with NDC and a team of artists led by artist Nehemiah Dixon to create a less-divided, more welcoming space by creating a monument from the barrier that would end the physical separation of the towns while acknowledging the community’s history. The result shows that while often historic and systemic, for many of the hostile architecture elements designed to restrict and divide, ample opportunity exists for them to be dismantled and re-imagined to create safer, more inclusive spaces.

Privilege at Play

“At its baseline, hostile architecture privileges one user over another by trying to create a scenario that will exclude a non-preferred user or behavior. It withholds an element of protection from particular users,” says Jennifer Goold, Executive Director of NDC.

When investigating who has the power to create that privilege (by determining behaviors that should be restricted, identifying those who are most likely to undertake those activities, and then installing features that exclude them) a clear picture of local hierarchy, environmental qualities, and stresses emerges.

Designers are hired to conceptualize our public space for local government leaders and real estate developers. While public space is intended to broadly serve the public good, the perspective of dominant populations gets embedded in the product through the design and construction processes. Hostile architecture can then be used to restrict the use of a public space based on race, age, income and other factors deemed undesirable.

The problem is that in addition to the inequity that is reinforced when using design to deliberately make one group feel unwelcome, adding these hostile elements often serves to make the space feel unwelcoming to all users.

Elements like protection and comfort are essential to attracting users to a public space. By removing those elements for one group of users, the space becomes inherently less welcoming for everyone. “If you take away features in order to exclude the non-preferred user, they are not available to the preferred users either and you just get empty spaces.”

When hostile architecture is used, instead of moving a public space up the hierarchy of usability to become a place where both preferred users and non-preferred users are comfortable, designers are instead moving the space down to the lowest common denominator.

“It’s usually low-resource areas where the city, municipality, or investor can’t afford or doesn’t understand how to build a high-quality space that has all of the necessary comfort criteria,” says Jennifer. “They are ashamed to have this space that just has nonpreferred users in it, and usually there is a scenario in which the elements of protection that would bring preferred users are very challenging to accomplish.” These scenarios include broader urban challenges like heavy vehicle traffic, lack of shade, low quality materials or seating options, or poverty leading to crime, illicit behaviors or de facto segregation.

“Hostile architecture comes into play in spaces that are already unhealthy and so far away from being functional spaces that the ‘solution’ is to just get rid of everybody,” says Jennifer. “When you’ve reached the stage where hostile architecture is showing up, you’re already at an ‘F’ in that space, and it needs an entire restart in terms of building a healthy public space culture.”

“When you’ve reached the stage where hostile architecture is showing up, you’re already at an ‘F’ in that space, and it needs an entire restart in terms of building a healthy public space culture.”

— Jennifer Goold, NDC Executive Director

Balancing Solutions

Mitigating the issues surrounding hostile architecture presents a difficult balance to strike, particularly when it comes to community design. In addition to the hostile design elements put in place by leaders and developers from a place of privilege, community members also often advocate for hostile design elements in public spaces during the community design process due the very real challenges to their feelings of safety.

“How do you address fear?” asks Merrell. “Fear is really the emotion that is the source of all of this hostile architecture, hostile design, and I think bringing in people to facilitate the social dynamics of public space and designing that part of the experience might be more powerful than whether or not there’s a bench.”

Public space design cannot alone fully address the systemic, root causes of those safety concerns, yet by keeping those challenges in mind, NDC strives to balance the need to create safe spaces with the desire to create inviting ones during the community design process.

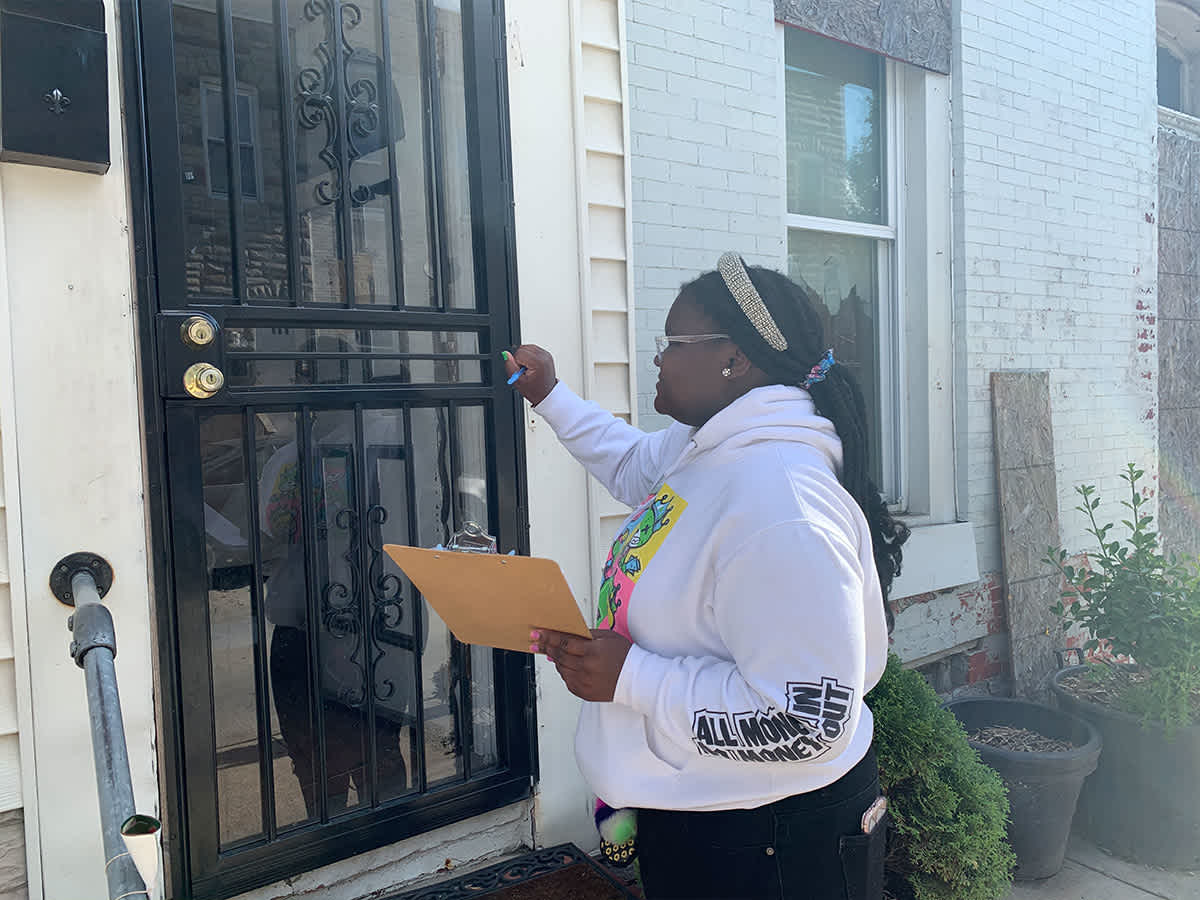

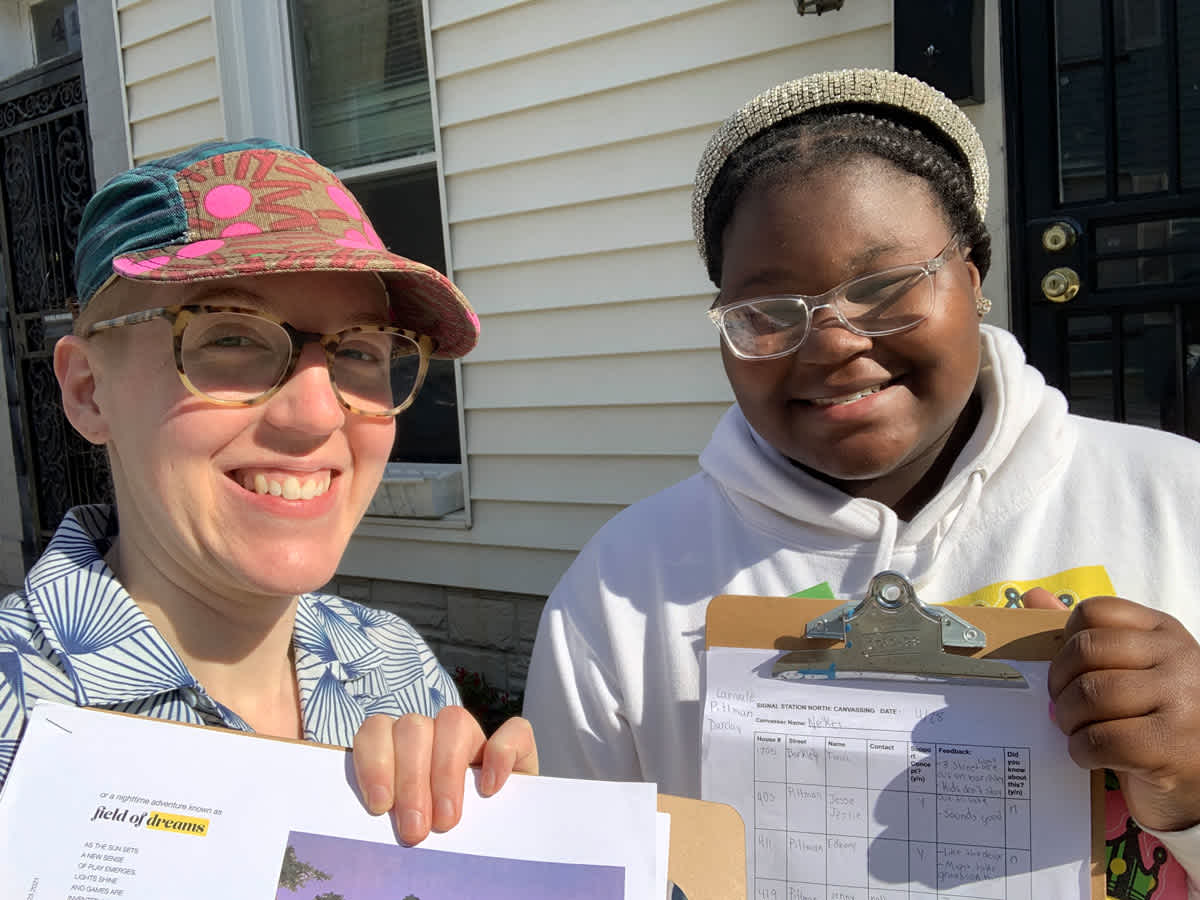

This balance came into play when NDC collaborated with Baltimore’s Station North neighborhood and local stakeholders, artists and designers to create the Signal Station North Project, a National Endowment for the Arts Our Town Grant and Central-Baltimore Partnership-supported effort to develop a lighting plan for the Station North Arts District in Baltimore City.

When imagining, and re-imagining, hostile architecture, lighting is not a feature that often comes to mind, yet lighting and its ability to make people feel comfortable or uncomfortable, welcomed or excluded is exactly what NDC delved deeper into through the project. The goal of Signal Station North was to create a lighting plan that would both provide visibility and promote community gathering, connection and placemaking. Using community listening and analysis as the foundation, the group spent two years devising the plan and understanding light and its many uses as part of that process.

One commonly accepted idea that the team was tasked to re-imagine was the idea that bright light produces greater safety in the public realm–a concept that is not supported by data. In reality, more light does not necessarily produce lower crime rates or even greater feelings of safety.

“Heading into the project, I was curious about that perception, and the fact that it isn’t really supported by evidence and what does that mean,” says Merrell, who worked as an NDC lead on the project.

“I wanted to try to understand how light impacts how we feel in the nighttime environment and how that's related to comfort and access to the public realm at night.”

— Merrell Hambleton, NDC Program Manager of Arts Planning and Cultural Programming

Through the Signal Station North project, Merrell was able to more fully understand the nuances of light and why brighter light is not automatically better light. Through community mapping and asking others to speak on their experiences, the community identified that in contrast to commonly held beliefs, very bright light often felt like surveillance. Brightly lit spaces can also cause adjoining spaces to be much darker because of the resulting shadow. Overlighting can support visibility, but it can also be used as a deterrent and a means of hostile architecture.

This aggressive use of lighting is made most apparent by mobile bright lights that law enforcement deploys in mostly lower-income areas of Baltimore City after a crime has occurred. These lights are intended to deter crime, but they are also blinding, loud, because they run on generators, and block sidewalks causing disruptions in the environment. In contrast, lighting instances that community members identified as making them feel comfortable included light spill from businesses and residences and light that creates a sense of space.

Among the many takeaways from the project was how light can be used in both a considerate and hostile manner. “Through that process, I came to understand how powerful learning about the impact of different infrastructure can be. I think the more you learn about something, it can change your idea of your own response to it,” says Merrell.

It's our position at Neighborhood Design Center that our community partners are experts. We genuinely believe that people know what they want and need in their environment; that is a critical grounding for the work that we do.

NDC is also finding ways to continue to implement education in the community design process. Merrell continues, “How do you make room for that expertise, and also invite engagement with different information about how design works, and how these different infrastructural elements operate?”

Creating education around the community design process is one way to curb some of the impetus to install hostile architectural elements in public spaces. Another part of being able to create more comfortable public spaces is not by just designing the physical infrastructure of the space, but considering how it is programmed and maintained. Creating programming that attracts a mix of other people to a space is one of the primary draws for people to show up to spend time and allows them to feel comfortable outside in an urban environment.

“There’s this sort of tension around not wanting people to stay in public spaces because it’s associated with criminal activity or loitering,” says Jennifer. “There’s a lot of tension between wanting to create comfortable, accessible public spaces and people being concerned about what those amenities might incur.”

NDC has successfully used the iterative/temporary approach to test ideas in contested areas where tension exists. NDC worked with community leaders and implementation partners from the 6th Branch and the Oliver Community Association on the development of the Bethel Street Playscape in Baltimore’s Oliver neighborhood. Neighbors expressed concerns about a proposed plan to add seating to the inner block park, with the prospect that people might sleep on the tables or that the seating would draw other potentially undesirable activities.

Through deeper conversation and a discussion of the positives and negatives, temporary, moveable seating was installed with the agreement that it would be removed if there were issues. NDC and partners designed colorful custom kids’ seating stools and purchased some off-the-shelf picnic tables to place around the site.

Over time, the use and relocation of these lightweight pieces of furniture showed that the community wanted the seating as it allowed parents a place to sit while joining their kids in the play area and somewhere to sit and read, converse, and gather.

Active use of the site continued to increase with the addition of flexible seating. The users also relocated the seating to preferred locations that maximized shade during after-school hours by creating a “bench” adjacent to the basketball court, which helped inform the final site layout.

Seeing that creating a more comfortable space outweighed the desire for hostile architecture to keep certain users away helped reinforce the vision and solidify support for a more permanent infrastructure in the space.

NDC faced a similar challenge when asked to help improve the facade of the Franciscan Center, an organization providing support and assistance to those who are economically disadvantaged, to enhance the safety, sustainability and hospitality of the building’s entrances. In conversations during the design process, finding a way to provide respite without enabling visitors to stay after dark came into question.

Our final recommendations included a structure with a retractable awning membrane to provide as-needed coverage. By using an intervention that could be altered, the organization could test their assumptions about how visitors may use the space if it does remain covered, and opt for more or less coverage overnight based on their observations.

Interventions like these can’t solve the baseline conditions for safety that need to exist to eliminate the desire for hostile architecture. Yet they can help to create small changes that allow for more comfortable spaces in urban communities.

“You can’t solve for hostile architecture across the whole neighborhood without neighborhood-scale change or city-scale change, but you can create pockets that bring in the elements necessary to create spaces that people really do use,” says Jennifer. “People will show up to invested spaces that have all of the elements that allow them to feel protected and comfortable.”

Hostile Architecture Resources

NDC Services that align with Hostile Architecture:

Architecture and Community Planning

The Architecture and Community Planning team at the Neighborhood Design Center specializes in participatory architectural design, place-based arts initiatives, and planning. Our team of architects, designers, planners, and engagement specialists hold strong commitments to design excellence, social justice, and responsive plans that prioritize community power and increased local self-determination.

Engagement and Facilitation

Community Planning

Architectural and Interior Design

Arts Planning and Cultural Programming

Engagement and Facilitation

Our staff is trained to make organization and community-scale decision-making easier and more inclusive. As facilitators, we design the engagement process, structure meetings and workshops, document the process, and provide findings to enable stakeholders to bring their expertise to projects. Your group will come away with a more unified vision and an enhanced ability to work as a cohesive team.

Youth engagement

Community and project visioning

Place-based strategic planning

Design Charrettes

Asset mapping

Train-the-trainer workshops

Coalition building

Engagement training

Arts Planning and Cultural Programming

Our placemaking team listens to the unique history of each neighborhood and proposes design and art solutions that anchor and amplify those stories in place. We can support you in identifying public art opportunities, artist selection, designing placemaking elements and events, or securing a historic designation for your building or neighborhood.

Public Art + Administration (includes artist residency programs, management of artist RFQs and RFPs), public art implementation

Placekeeping and Placemaking

Historic preservation

Place-based identity and designs

Public space design

Community Landscape Design

We create accessible outdoor spaces that respond to the community’s wants and needs, from single lots to neighborhood greenspace networks.

Neighborhood Parks and Pocket Parks

Playgrounds and Playscapes

Community Gardens

Interpretative Trails and Wayfinding (on/off road trails with educational and directional signage)

Vacant Lot projects

Neighborhood Greening Plans

For More Information

Organizations and Funders

Related Reading

Additional Publications

Ball K, Haggerty K, Lyon D (eds) (2012) Handbook of Surveillance Studies. New York: Routledge. Crossref, Google Scholar

Chellew C (2016) Design paranoia. Ontario Planning Journal 31(5): 18–20. Google Scholar

Davis M (1990) City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. London: Verso.

de Fine Licht K (2017) Hostile urban architecture: A critical discussion of the seemingly offensive art of keeping people away. Etikk I Praksis: Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics 2: 27–44. Crossref, Google Scholar

Dovey K (1999) Framing Places: Mediating Power in Built Form. London: Routledge.

Flusty S (1994) Building Paranoia: The Proliferation of Interdictory Space and the Erosion of Spatial Justice. Forum Publication No. 11. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design. Google Scholar

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and Punish. New York: Vintage. Google Scholar

Goold B (2004) CCTV and Policing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar

Howell O (2001) The poetics of security: Skateboarding, urban design, and the new public space. Urban Action Journal, San Francisco State University, 2001. Google Scholar

Koskela H (2003) ‘Cam era’: The contemporary urban panopticon. Surveillance & Society 1(3): 292–313. Crossref, Google Scholar

Léopold L (2013) Cruel Designs, The Funambulist Pamphlets, vol. 7. New York: Punctum Books. Google Scholar

Levin TY, Frohne U, Weibel P (eds) (2002) CTRL Space: Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Google Scholar

Low S (2003) Behind the Gates: Life, Security, and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York: Routledge. Google Scholar

Lyon D (2001) Surveillance Society: Monitoring Everyday Life. Buckingham: Open University Press. Google Scholar

Marx GT (2015) Windows Into the Soul: Surveillance and Society in the Age of High Technology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Google Scholar

Maxwell K (2014) Buzzword: Hostile architecture. Macmillan Online Dictionary. Published online 26 August 2014. Available here

Minton A (2012) Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First-Century City. London: Penguin. Google Scholar

Mitchell D (2014) The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: Guilford. Google Scholar

Monahan T (2010) Surveillance in the Time of Insecurity. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Google Scholar

Morton E (2016) The subtle design features that make cities feel more hostile. Atlas Obscura., 5 May. Published online 5 May 2016. Available here

National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty (2014) No Safe Place: The Criminalization of Homelessness in the United States. Available here

Newman O (1972) Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design. New York: The Macmillan Company. Google Scholar

Norris C, Armstrong G (1999) The Maximum Surveillance Society: The Rise of CCTV. Oxford: Berg. Google Scholar

Petty J (2016) The London spikes controversy: Homelessness, urban securitisation and the question of ‘hostile architecture.’ International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 5(1): 67–81. Crossref, Google Scholar

Quinn B (2014) Anti-homeless spikes are part of a wider phenomenon of ‘hostile architecture’. The Guardian, 13 June. Available here

Rosenberger R (2014) How cities use design to drive homeless people away. The Atlantic online, 19 June. Available here

Rosenberger R (2017a) Callous Objects: Designs Against the Homeless. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Google Scholar

Rosenberger R (2017b) On the hermeneutics of everyday things: Or, the philosophy of fire hydrants. AI & Society 32: 233–241. Crossref, Google Scholar

Rosenberger R (forthcoming) Hostile design and the materiality of surveillance. In: Wiltse H (ed.) Relating to Things: Design, Technology and the Artificial. London: Bloomsbury. Google Scholar

Savičić G, Savić S (eds) (2013) Unpleasant Design. Belgrade: G.L.O.R.I.A. Google Scholar

Schindler S (2015) Architectural exclusion: Discrimination and segregation through physical design of the built environment. The Yale Law Journal 124: 1937–2024. Google Scholar

Smith N (1996) The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. London: Routledge. Google Scholar

Smith N, Walters P (2018) Desire lines and defensive architecture in modern urban environments. Urban Studies 55(13): 2980–2995. Crossref, ISI, Google Scholar