What We Do

Building equity through community-led design since 1968.

Why We Do This Work

We support the growth of healthy, equitable neighborhoods through community-engaged design and planning services.

By providing the tools, expertise, and partnerships necessary to realize neighborhood visions, we support broad participation in the evolution of the built environment, positioning historically disinvested neighborhoods to attract future investment.

NDC projects are collaborations between residents, community stakeholders, design professionals, local government agencies, fellow nonprofits, and our staff. Together we lay the groundwork for improving blocks, renovating parks and school grounds, reclaiming abandoned structures for community use, and revitalizing commercial districts.

We believe that these unlikely partnerships provide mutual benefit — it provides our volunteer designers with invaluable experience and helps them think about their practice in a new, more equitable way, while also exposing community members to the behind-the-scenes process of change.

We believe...

the community is YOURS.

Why Place Matters

Our work focuses on public and shared spaces—the environments we occupy together. Why? Because well-designed public spaces make communities safer, happier and healthier. In a 2017 study in Philadelphia, researchers found that greening vacant lots in neighborhoods below the poverty line resulted in:

29.9% reduction in gun violence

21.9% reduction in burglaries

13.3% reduction in crime over all

In a survey of people living near the greened lots, researchers found:

41.5% fewer participants reported feelings of depression

50.9% fewer participants reported feelings of worthlessness

Source: “Citywide cluster randomized trial to restore blighted vacant land and its effects on violence, crime, and fear” by C. Branas, E. South, M. Kondo, et al.

Our Values

We are committed to building just places. We are courageous in our curiosity. We are inclusive in our collaboration. We design for just futures.

At the Neighborhood Design Center, we come to our work with open minds and a readiness to ask hard questions, listen deeply, and change course when necessary. We use the criteria in our Values document to guide where we work, the projects we take on, how and where we invest resources, and the culture of our own practice. Read more:

Our Impact

of NDC partners said our process strengthened their community association

we design over 5,000 new tree plantings each year

each year our volunteers invest more than $200,000 worth of hours

Our History

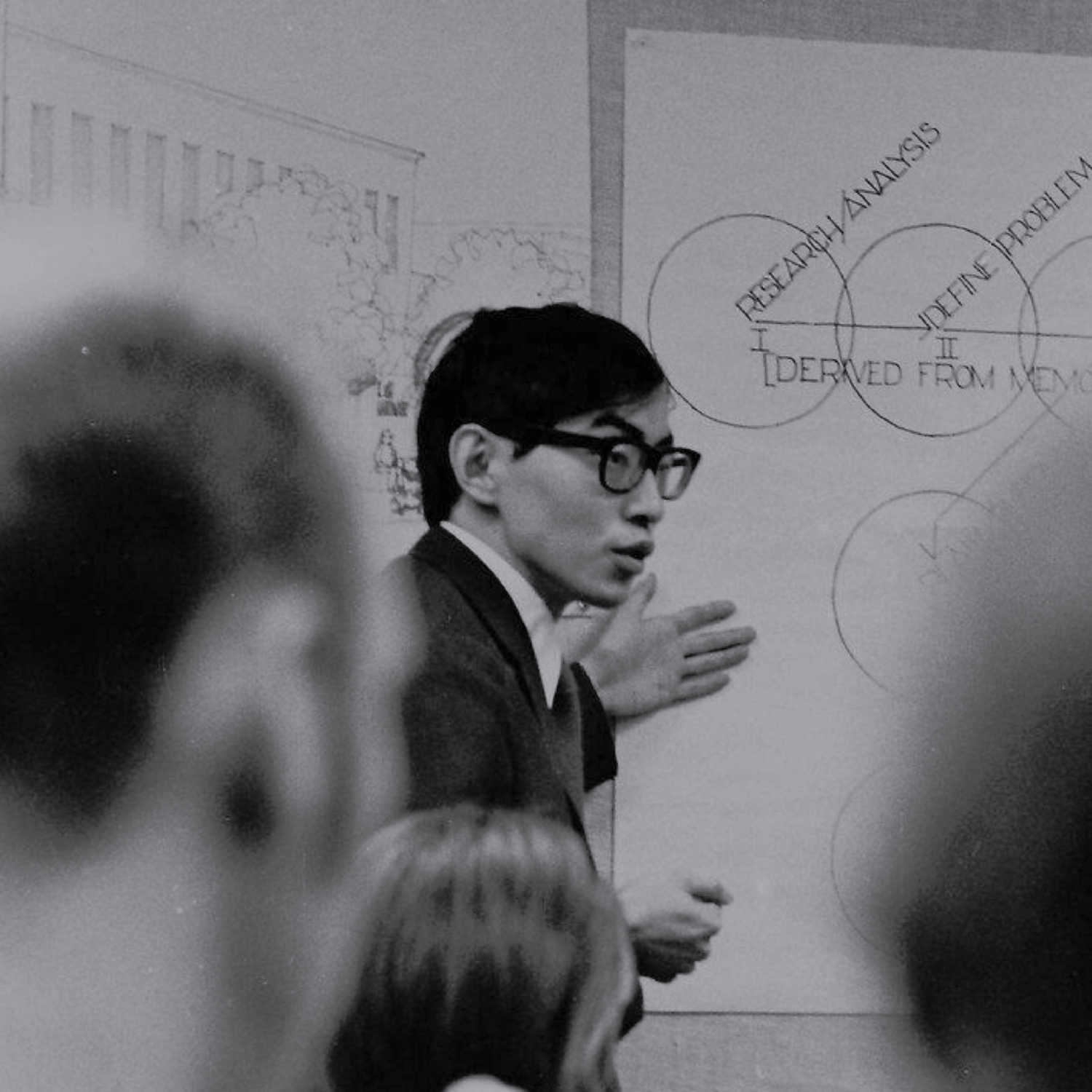

On June 24, 1968, in the midst of the civil rights movement, Whitney M. Young, Executive Director of the Urban League, stepped to the podium to address the 100th Convention of the American Institute of Architects.

“You are most distinguished by your thunderous silence” in the face of urban disintegration, he challenged. “You share responsibility for the mess we are in terms of the white noose around the central city. It didn’t just happen. We didn’t just suddenly get this situation. It was carefully planned.” His words were not comforting, nor were they meant to be. From Young’s speech sprang a national call to action among architects, and nonprofit “design centers” opened in cities across the United States.

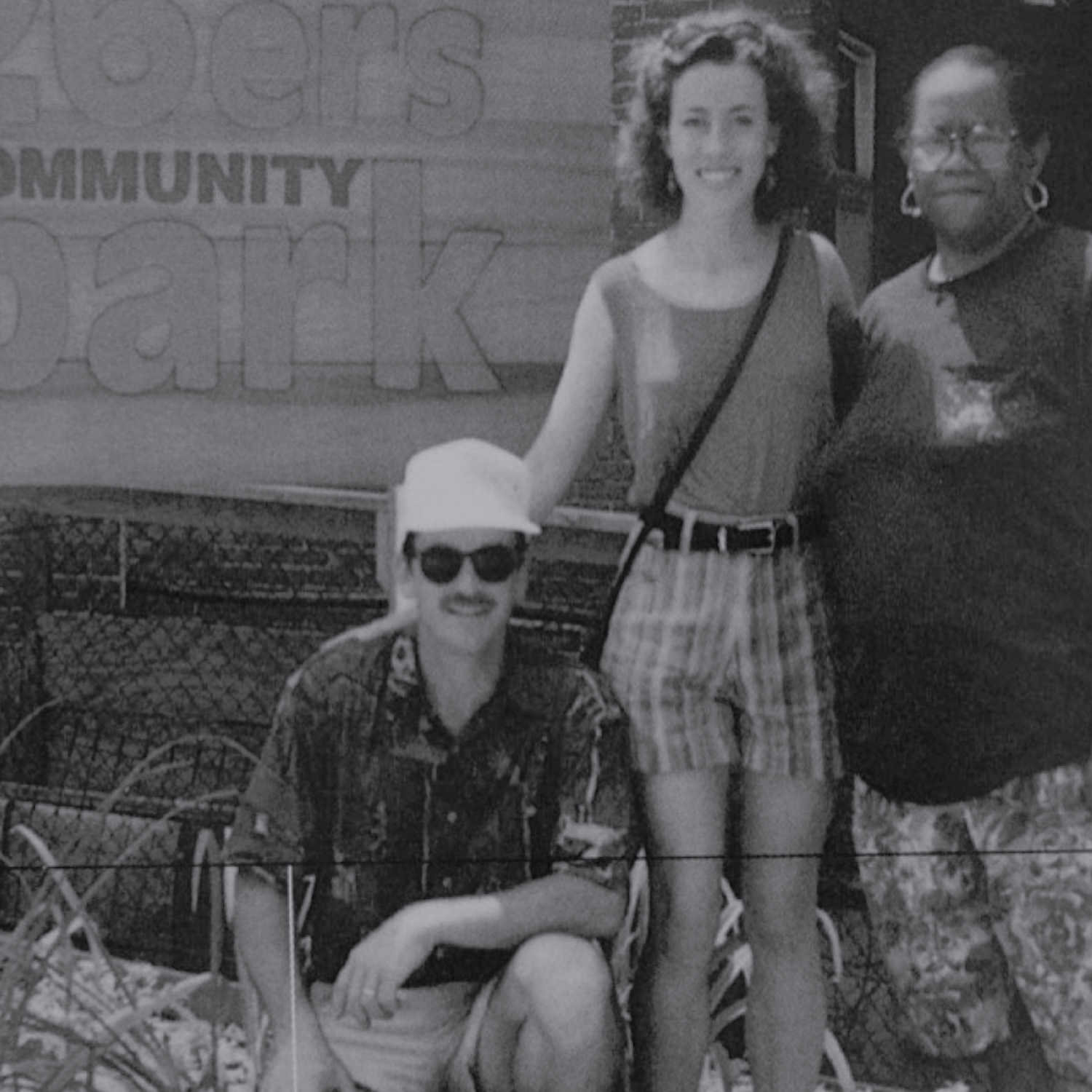

In the fall of that same year, a group of architects in Baltimore took this challenge and began working with low and moderate income communities to rebuild after the riots and white flight that swept the city in the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination. Thus was the birth of the Neighborhood Design Center.

The volunteer architects started simply, working with residents and a few nonprofits to develop for community centers, playgrounds, affordable housing, and neighborhood master plans. The goals of the architects were to use the projects as a community organizing tool, a means of advocating for urban development, and as a tool for increasing investment in Baltimore’s neighborhoods.

By the early 1970s, what was strictly a volunteer organization could not keep up with the growing demand for services. Funding was secured through the efforts of Charles Lamb, FAIA (founding partner with the architectural firm RTKL) and NDC hired its first paid staff to manage the requests and projects. Since then, the office has functioned in this manner – maintaining a small number of paid staff that are supported by a large number of volunteers.

In 1993, NDC expanded outside of Baltimore, opening a second office in Prince George’s County to serve the older, lower-income communities surrounding Washington DC. The expansion of NDC allowed the organization to draw from a regional volunteer base—from Northern Virginia to suburban Baltimore—as well as assist various statewide initiatives.

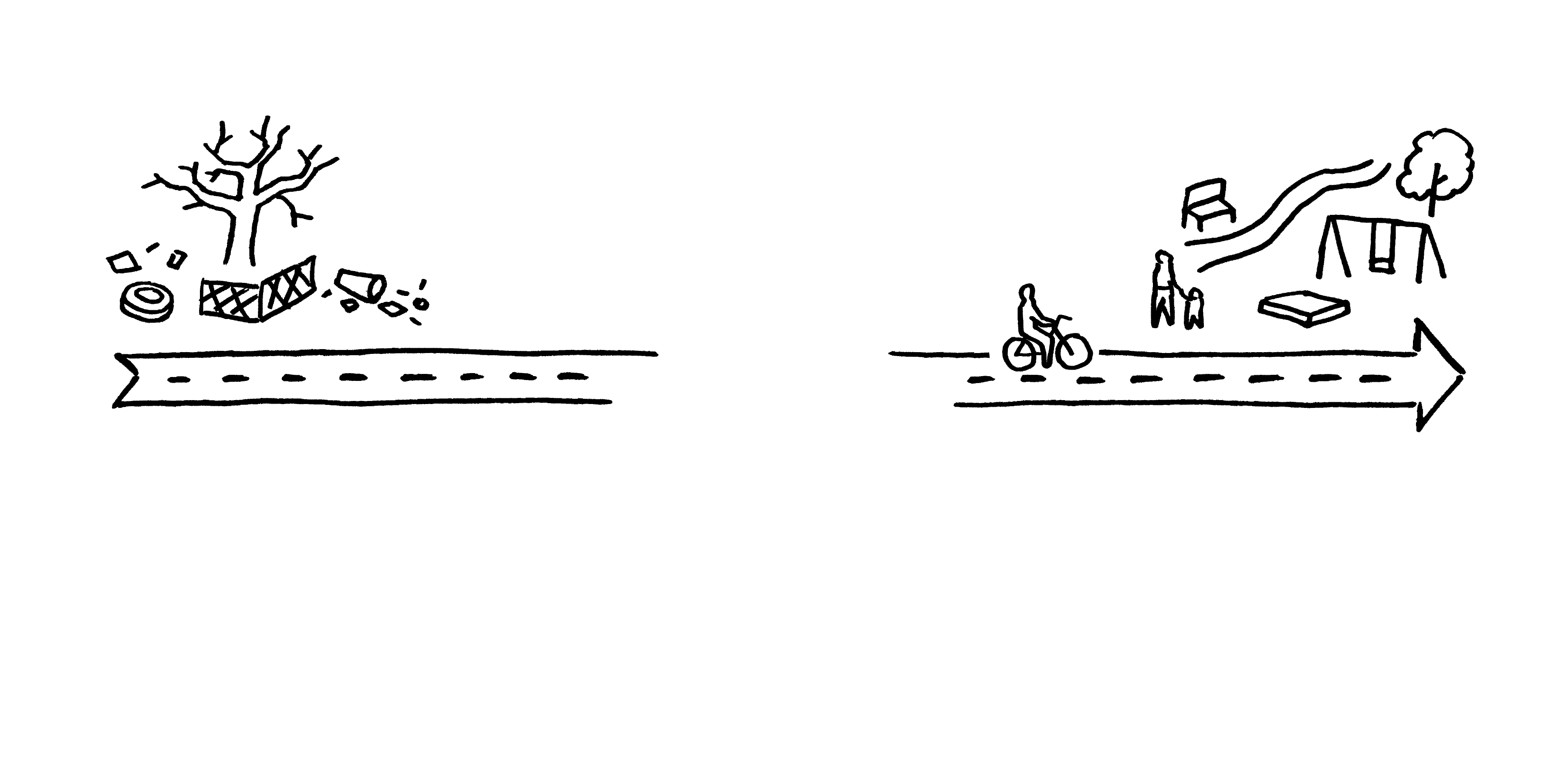

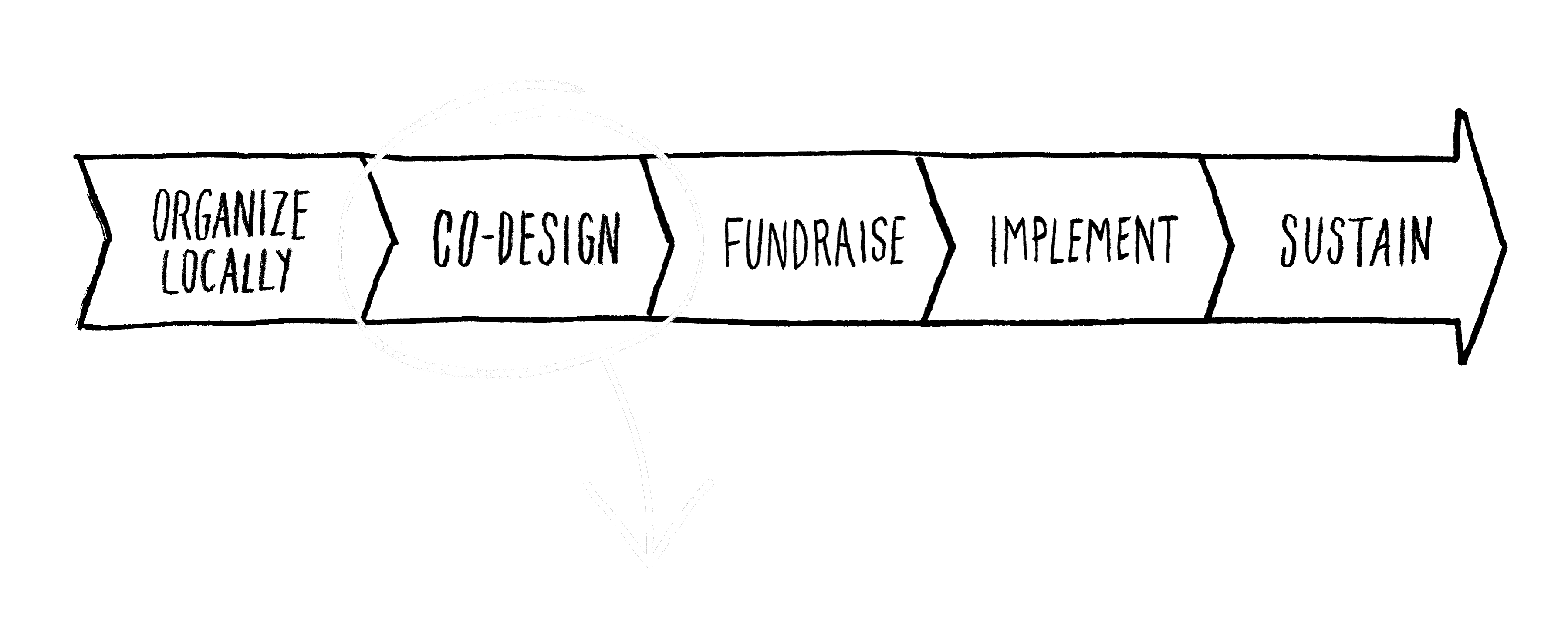

Our Process

Since 1968, we’ve practiced co-design, a process built on participatory decision making at all levels.

We bring everyone to the table. The more inclusive the process, the better the design, the stronger the buy-in, and the longer-lasting the project.