Gethsemane United Methodist Church: Exploring how campus can best support community

What We Did

- Community Engagement

- Research

- Site Analysis

- Master Planning

Partners

- The Capital Market

- Gethsemane United Methodist Church

Supporters

- Prince George’s County Department of Housing and Community Development

Since its inception, the church has had a legacy of community engagement.

Gethsemane United Methodist Church (GUMC) stands on top of a hill on Addison Road in Capitol Heights, Maryland. The masonry building was constructed in 1961 and officially became Gethsemane United Methodist Church in 1980, but its roots in the community hail back to the 1870s.

GUMC partners to address social justice and equity issues to transform the global and local community into a more just, inclusive, and supportive space.

Their community-based services include

a fellowship hall and sanctuary for local events

a daycare center

a food pantry

kitchen space for The Capital Market (TCM), a community-based farmer’s market that provides healthy, affordable food options to Capitol Heights residents

The Challenge: Address decades of separation from neighbors.

In recent years, area shifts have fueled a disconnect between the church community and the local one.

More church members drive to GUMC from outside Capitol Heights, while those in the surrounding neighborhoods attend churches elsewhere, leading the congregation to be made up of fewer local residents.

How might the campus be redesigned to reconnect with the community and better support everyone’s needs?

Location, both an opportunity and constraint.

The church lies within a mile of the Blue Line, a transit line of the Washington D.C. Metro system. This proximity would allow GUMC to leverage the renewed interest in the area and bring a valuable counterbalance of community-led development to the traditionally top-down approach of the Blue-Line investment.

However, the church is tucked away from the road, on a hill, which creates a physical separation from the community. The location is also adjacent to a streambed that requires environmental protection, which creates another potential challenge.

The Vision: Bridge gaps with thoughtful redevelopment.

Together with the Source Collaborative, a committee of community partners and GUMC congregants partnering with Wesley Theological Seminary to develop a long-term model for church campus growth, the congregation began to assess how to re-imagine their indoor and outdoor space to better service community needs.

An initial plan for redevelopment focused primarily on adding senior housing to the site. The church campus included a supportive housing facility years ago, and recreating it present-day many felt would be a way of returning to GUMC’s community-oriented roots. Others supported bringing in additional resources to support the broader community, and as conversations about the redesign continued, decision-makers began to fall into opposing camps.

The project needed an external mediator, as most of those involved in the discussion were members of the church who fell on opposite ends of the spectrum. NDC was brought into the project to be an outside voice that could see and validate both sides. We would also provide recommendations for other resources, help build capacity, and transform feedback into plans.

“Our goal throughout the process was to create spaces for everyone to feel a sense of belonging.”

— Brittney Drakeford, Community Planner and GUMC Trustee

The Team

Led by NDC Program Manager Sophie Morley and Program Coordinator Angelica Arias, NDC assembled a group of volunteer designers with diverse professional backgrounds to assist with the effort.

Project Volunteers

Ugo Njeze - Graduate Student, The George Washington University - Sustainable Urban Planning Master of Professional Studies

Roger Isom - Public Health Analyst at DC Department of Health

Brian Cubin - Senior Education Designer at Education Design Lab

Upasana Kaku - Graduate Student, University of Maryland - School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation

Jude Abijah - Undergraduate Student, Northwestern University - School of Education and Social Policy

NDC worked with a group of very involved church members across age groups, lifetime Prince George’s County residents, and active community participants.

Project Leaders

Brittany Drakeford - urban planner, faith community member and community activist

Ashley Drakeford - faith community organizer, community garden coordinator and on-the-ground organizer of The Capital Market

Kyle Reeder - holds expertise in transportation, justice, density, and understanding how continuous change can be in support of environmental and community justice work.

Reverand Ronald Triplett - Pastor of GUMC who is invested in ensuring that Gethsemane is in service and connected to the larger community.

Community Engagement

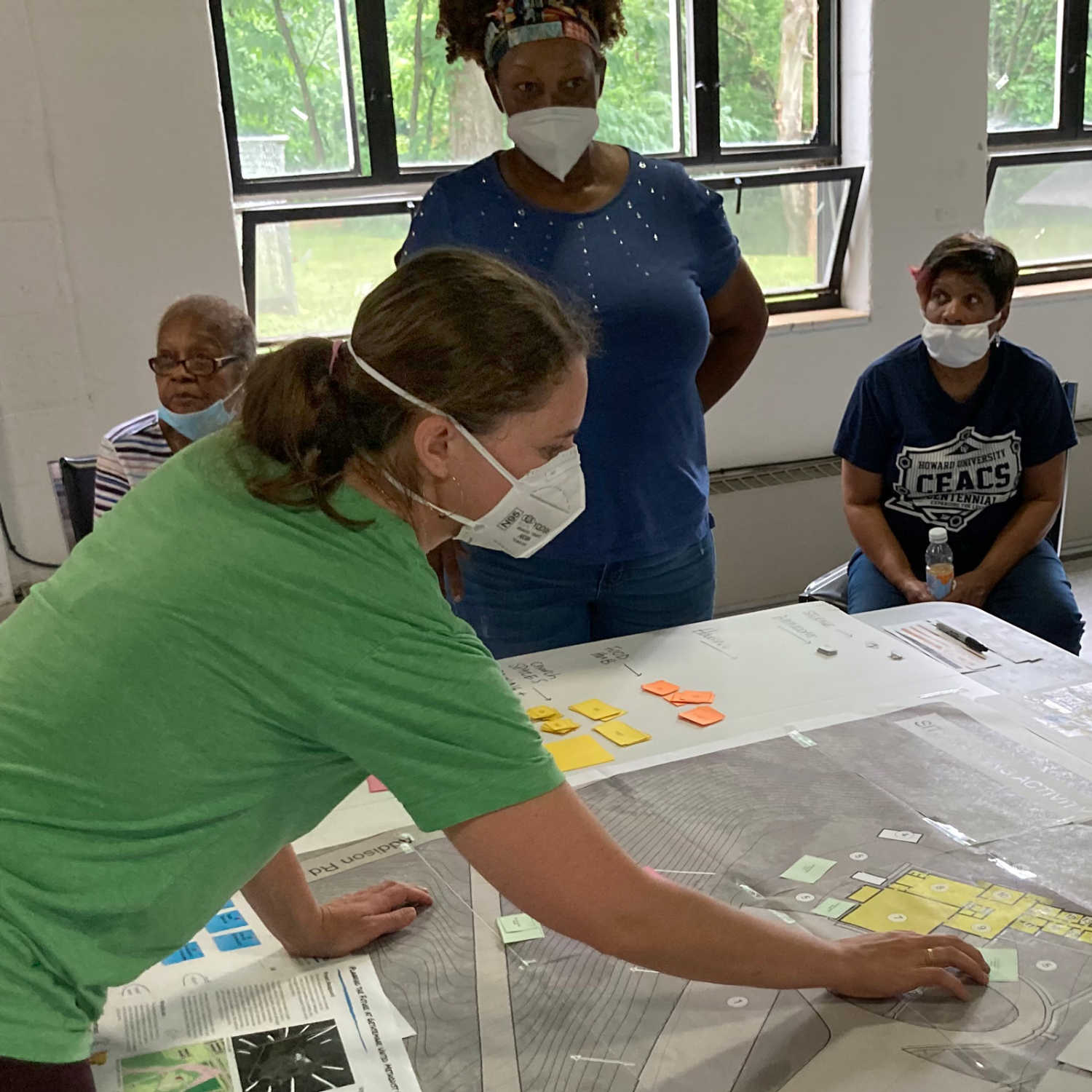

The Neighborhood Design Center conducted workshops, focus groups, and surveys and held individual conversations to ensure an equitable community engagement process targeting multi-generations to shape the church’s future.

The survey served as evidence of community needs, highlighting issues like the lack of grocery stores, experiences of violence and crime, and the need for resource centers and working spaces.

Church members and residents in the broader community worked together to paint the church’s walking labyrinth banner that NDC helped design. The event was an opportunity for people to engage in a mapping activity and share ideas.

What stakeholders said they’d like to see

“A visit to GUMC will be uplifting, serene, calm, inviting, like a park, places to walk and sit to have conversations; walking trail.”

“I would like to see a Senior facility where young folk can collaborate with seniors on the land.”

“We want healthy foods — gardening and growing vegetables on our property.”

Identifying Community Gaps

A list of needed spaces emerged, including spaces for youth activities and programming, community gardens and green space, a food hub, senior or multifamily housing, a health center, and a resource center or library.

NDC also collaborated with the community to create a vision statement for the project, outlining the objective of creating “a safe, welcoming and comfortable space where everyone is valued and supported to grow and thrive.”

The community engagement also required participants to address challenging questions about how to best support that vision through the project. For example, community conversations shed light on the fact that many seniors also care for grandchildren. This reality presented the question of whether creating housing dedicated to seniors only, which would then exclude grandchildren, lived up to GUMC’s mission as a church

Apart from the goal of connecting with the community, one of the priorities of the redesign is to maximize the use of available space on the site. Pedestrian access, including ADA compliance, is crucial for senior and youth accessibility. Additionally, the church desired safe and convenient connections for individuals walking from the road to the hilltop site.

“Senior housing can be affordable, but could it be more affordable if you have people of all ages living together? Is intergenerational housing a way to build a beloved community?”

— Brittney Drakeford

Site Analysis

The NDC team analyzed existing conditions, zoning and use, and feasibility for future development. While the streams and slopes create development constraints, there is still space to create outdoor gathering spaces, additional parking, a resource center, and open spaces for gardening or outdoor activities.

Research and Case Studies

For inspiration, we did extensive research into other faith-based organizations that have developed and repurposed properties. Since affordable and senior housing was part of the community’s vision, we had congregants visit affordable housing sites in the region, watched videos during church services about housing needs, and met with Dr. Joe Daniels, an area pastor and professor from Wesley Theological Seminary whose church led the development of affordable housing units.

Two design plans to consider

Option 1

remodel and expand the existing GUMC footprint and prioritizes the creation of new outdoor spaces for both the church and the broader community.

Option 2

presents a more ambitious scenario, including a full build-out for the site to create a new community comprising GUMC facilities, green space, and new housing.

The Future: The congregation is moving forward with both options and securing funding for the project build.

As the project moves into its next phase, NDC worked with the Source Collaborative to create recommendations for capacity building so that Gethsemane United Methodist Church can take the project and move it forward after our work is complete.

As the project has many different components, they are applying for grants to begin work on some parts of the project and have been accepted into Enterprise Community Partners’ technical assistance program, which provides pre-development funds.

In addition to the creation of the two designs, the project’s success is evident in the shifting perspectives between the diverging community positions to agree on the future vision of the site. Initially, many of the seniors in the congregation focused solely on the senior housing vision, while the younger members had a broader vision, including a resource center and outdoor gathering spaces. Overall, they also had to tackle some negative misperceptions surrounding affordable housing and challenge assumptions through education, data and evidence.

Through various engagement activities, the two groups were able to converge around the community’s needs to agree on a way forward. The shift in perspective was a significant accomplishment, as it brought the different generations together and broadened their vision for the site’s future development.

“Churches are important community assets and anchor institutions,” says Brittney. “It’s important for them to think about how they’re using their spaces.”